This content is also available in: German

Making the car CO₂ standards fit for the electric age

Under the current fleet standard regulation, the allowed emissions of combustion-powered cars are getting out of control as more and more zero emission vehicles enter the fleet.

Preface

When the European Commission tabled its proposal for the first CO2 emission standards for passenger cars in 2007, the idea of electrifying the car fleet seemed far away. Although the first Tesla roadster had already been built, its impact was yet to be felt. And should anyone have suggested that the entire transport sector – nay, the economy as a whole – was going to have to be completely decarbonized, they would have been laughed at. That is why the proposal on CO2 from cars came to be drafted with a combustion-powered car fleet in mind. Electric vehicles were an afterthought – a theoretical concept, to be dealt with at some later stage. They were counted as zero-emission cars, not only because that is what they are within the scope of the legislation1, but also because there was neither time nor motivation to think about them more deeply. Thirteen years on, and two revisions of the legislation later, that fundamental design principle remains unchanged. And that is starting to be a problem.

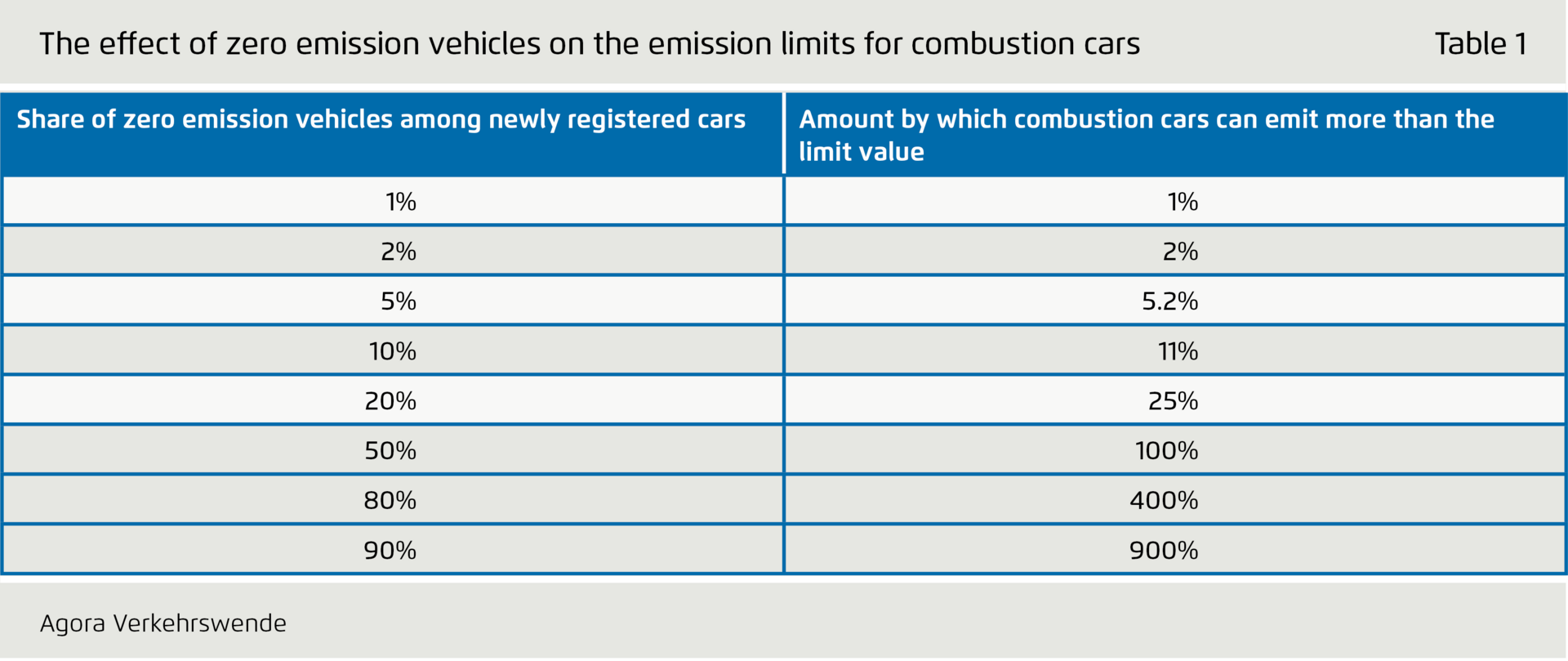

The electric chickens are coming home to roost. The problem is that combustion cars and electric cars are very different things when it comes to emissions. The legislation limits the average emissions of all cars taken together, both combustion cars and zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs). This gives a lot of slack to the combustion cars. For each ZEV that a manufacturer sells, they can sell a combustion car that emits twice the manufacturer’s emissions target while still complying with the legislation. Looking at all the vehicles together that a manufacturer sells in a year, a share of 5% of ZEVs allows the other 95% of combustion cars to emit 5% more on average than the target. For 10% of ZEVs, that surplus rises to 11%. For higher shares of ZEVs (and they will have to rise to 100% at some point) this effect becomes large2, as shown in the table.

As the share of ZEVs approaches 100%, the emission levels of combustion cars go through the roof. This does not mean that the emissions of the real cars will actually rise to such humungous levels. But they will be allowed to, while still being in compliance with the legislation, so in practice they will no longer be constrained in their emissions. That is the opposite of what the legislation intends: the limit values for CO2 are going down all the time. Let us explore how this could play out in the coming years.

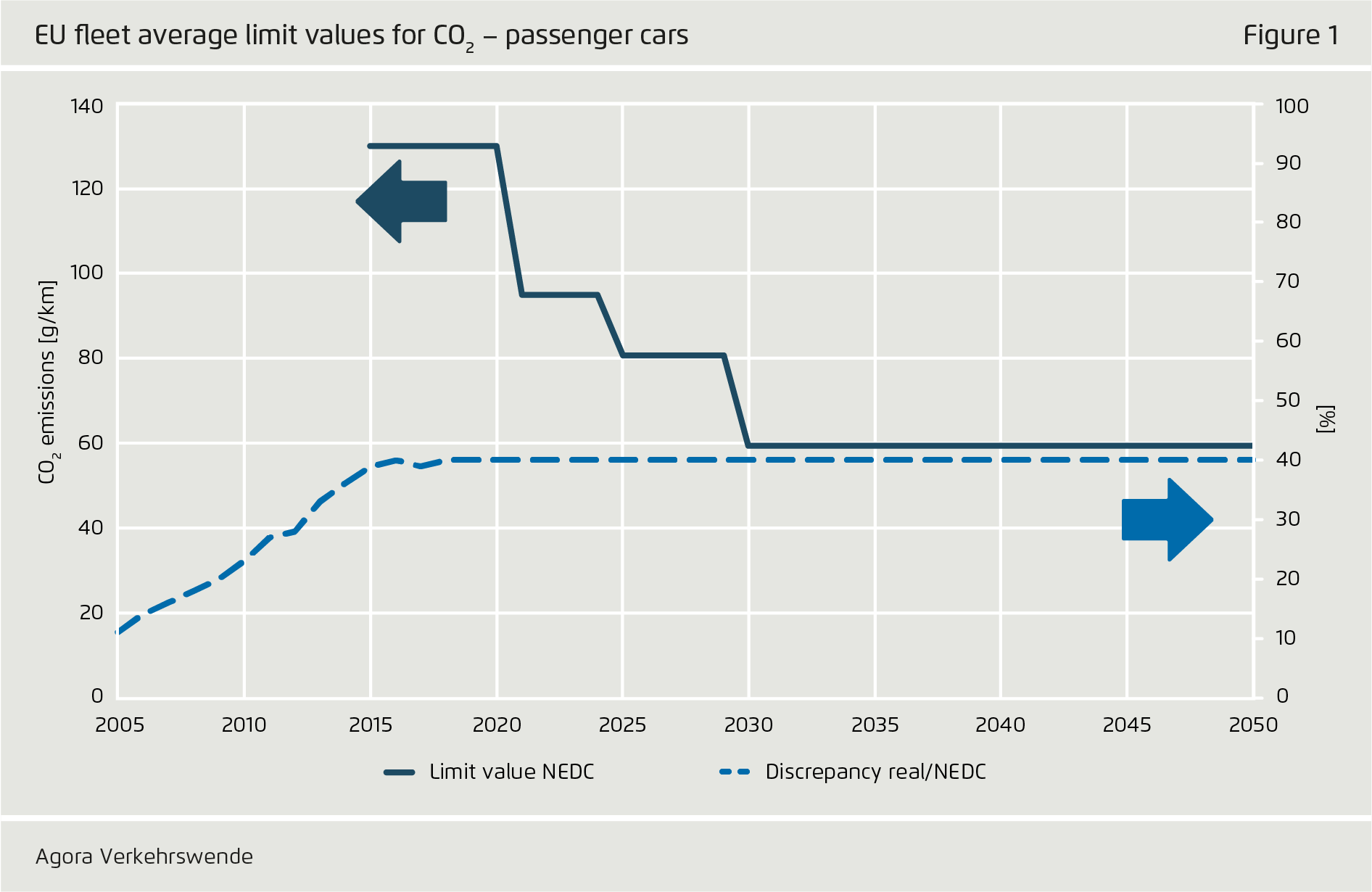

There is no way but down – at least that’s the intention. The original legislation3 laid down the limit value of 130 grams of CO2 per kilometer (g/km) from 20124, but it already specified a further stage of 95 g/km from 20205. A subsequent review resulted in two further reduction steps, first in the year 2025 by 15% compared to the 2021 value, and then in the year 2030 by 37,5% compared to the 2021 value. That last reduction looks really tough. Not long after it was agreed in December 2018, Volkswagen announced that it would convert its entire offering in the light-duty vehicle sector to electric drive in the coming years. Other manufacturers were less unambiguous but they also started to prepare for a fundamental shift in the drive technology that will power their vehicles in the future, away from combustion engines.

The dark line in the graph illustrates the downward staircase of limit values in the coming years. Readers familiar with the subject will notice that I have conveniently continued using today’s metric for the CO2 emission level of a car. In reality, the measuring process underlying this value is currently being changed6 which will make the CO2 values more realistic and thus, higher. This procedural change is the reason why the new standards for 2025 and 2030 have only been expressed as percentage reductions from 2021: the absolute values will only be known once the 2021 values under the new test method are available.

To get around this technical complication, let us look instead at the real-world emissions of the vehicles. Those aren’t so well-defined, but consistent evidence shows that they are higher than the test values, and that this discrepancy has been growing over time7. Because of the increasing legal pressure to reduce emissions, I am assuming that from now on it will not grow any further from the level of 40% above the results of the old NEDC test. But I’m not assuming that it will shrink either, see the blue dashed line in the graph above. Once the new WLTP test procedure is being applied, the official test results, and hence the limit values, will be higher by maybe 20 or 30 per cent. Since WLTP values are more realistic than those under the NEDC, their discrepancy to the real emissions will shrink, but it is unlikely to shrink to zero8. For simplicity, let’s just assume that the real emissions will remain at the level of NEDC plus 40%. That’s unlikely to be exact, but good enough for our subsequent line of reasoning.

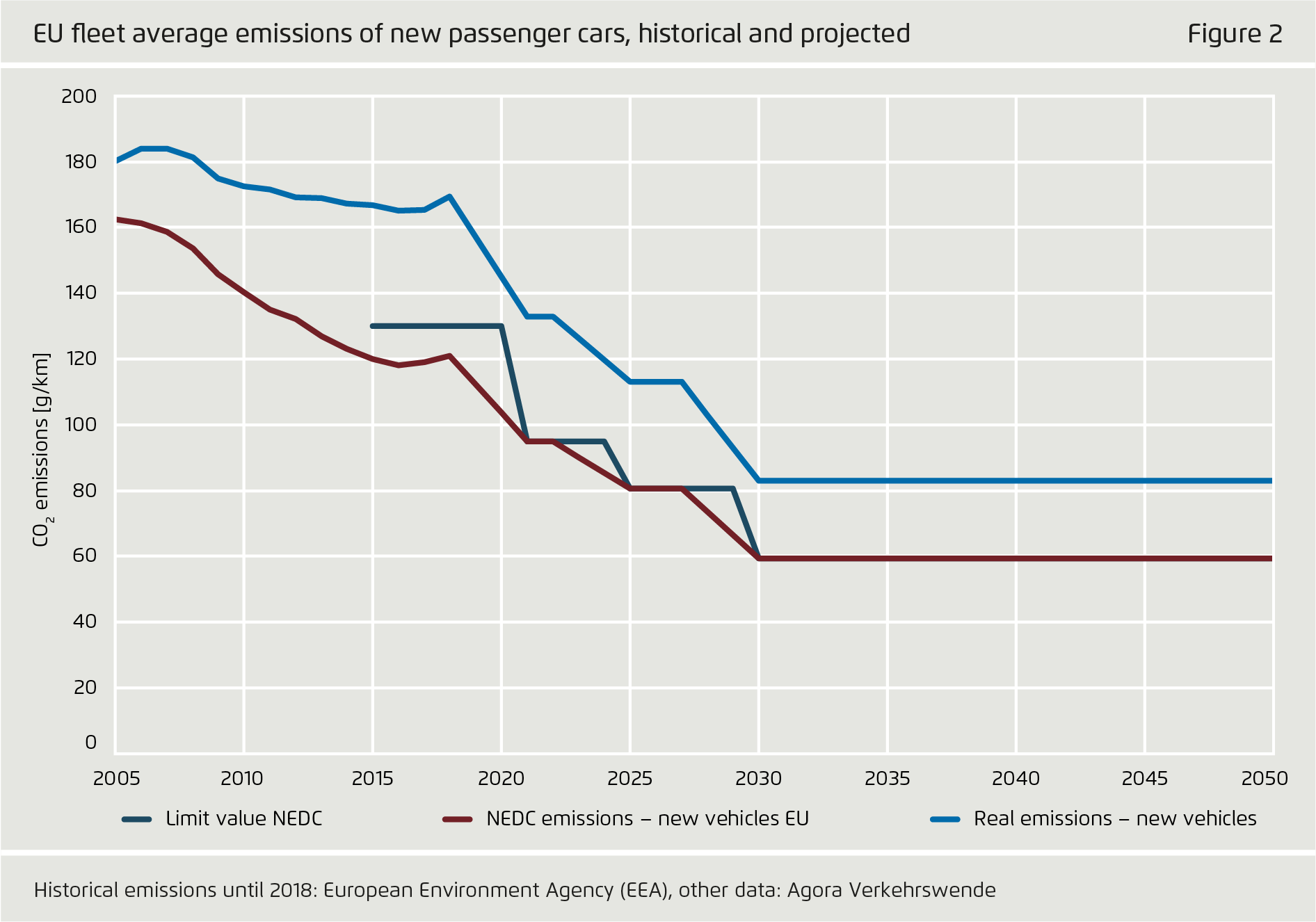

The next graph shows what this means. The NEDC fleet average values, shown in brown, are the actual values from the official monitoring until 2018. After that I am assuming that the manufacturers will do just enough to meet the limit values, and that two years before each tightening they start adapting their new cars to the next level. The corresponding real-world emission levels are shown by the blue line.

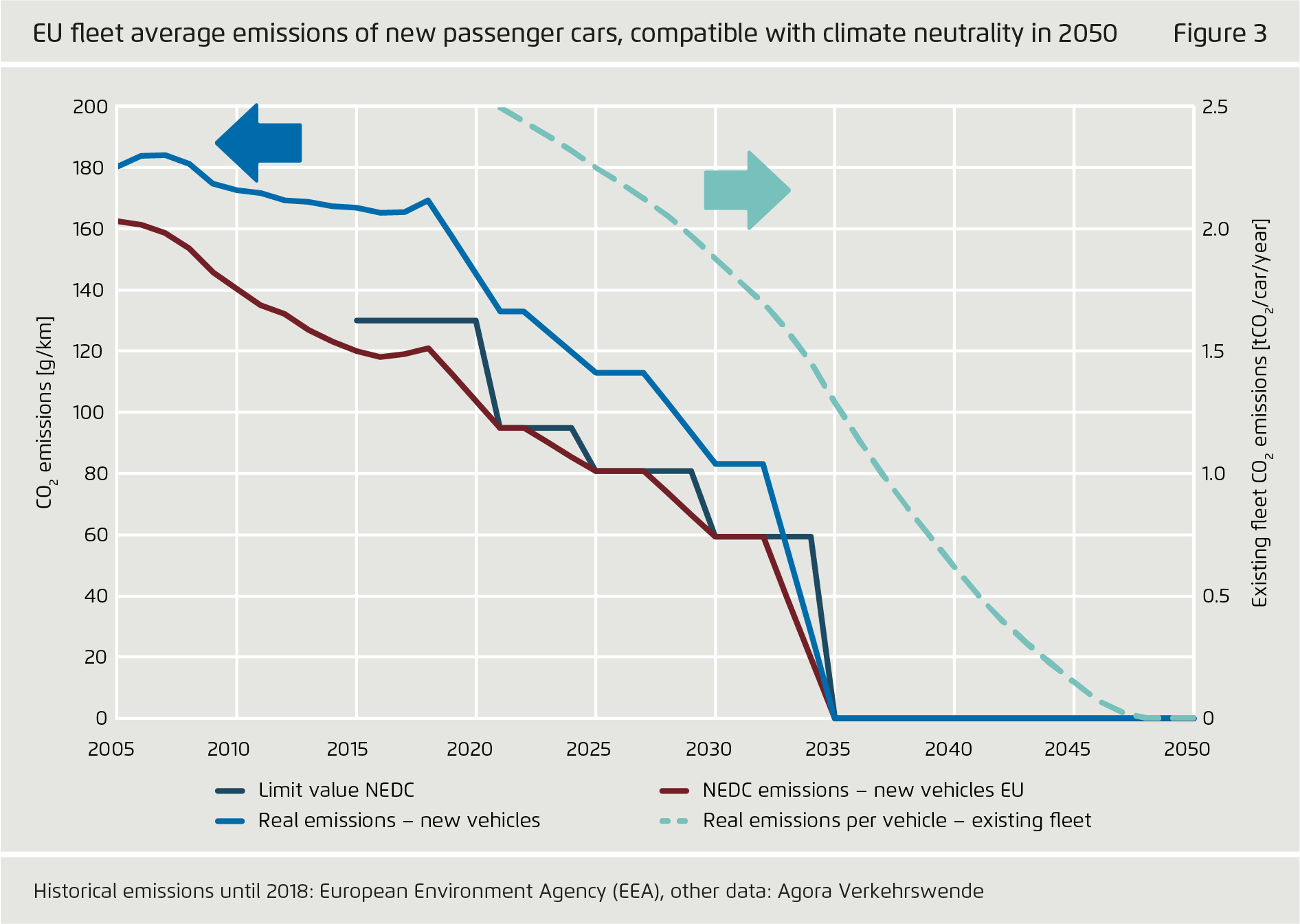

You ain’t seen nothin’ yet. Given where we are today these reductions look pretty tough. And yet, bigger changes are afoot as a consequence of the Paris climate conference in 2015 that established the goal of holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C. It took a while for the implications of that agreement to trickle through. By now it is widely recognised that to reach this goal, the industrialised countries will have to become CO2 neutral by 2050 at the latest. The new President of the European Commission, Ms von der Leyen, placed this objective at the heart of her European Green Deal9 and it was endorsed by the EU heads of state and government on 13 December 2019.

Let’s see what this means for cars. By the year 2050, the entire fleet of cars on the road will have to be emission-free. Since cars last on average about 14 years, the last combustion car10 will have to be sold sometime around 2036 – or sooner since some cars reach a higher age. As a consequence, we have to insert another step in the limit value staircase, a limit value like no other: zero. In the graph I’ve chosen the year 2035 for this cliff edge because the resulting emissions of the whole car fleet11 then become zero slightly before the target year of 2050, as shown by the green dashed curve.

This gives us a taste of what may be in store at the next review of the Regulation on CO2 from cars that will be proposed already in June 2021, according to the European Green Deal. One could imagine that it was graphs such as this that persuaded the car makers that there really was no way around the electrification of the drive train. Plus, they need it much earlier than the 2030’s, and not just because of the Chinese policy on zero emission cars12. Already the first step of tightening the standards to 95 g/km this year and next is expected to require a sizeable level of electrification13. For those of us who want to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions from transport, this is welcome because it signals that the technical requirements for a full decarbonisation of the sector are now really being developed. However, if the format of the legislation remains unchanged it will have unwanted side effects.

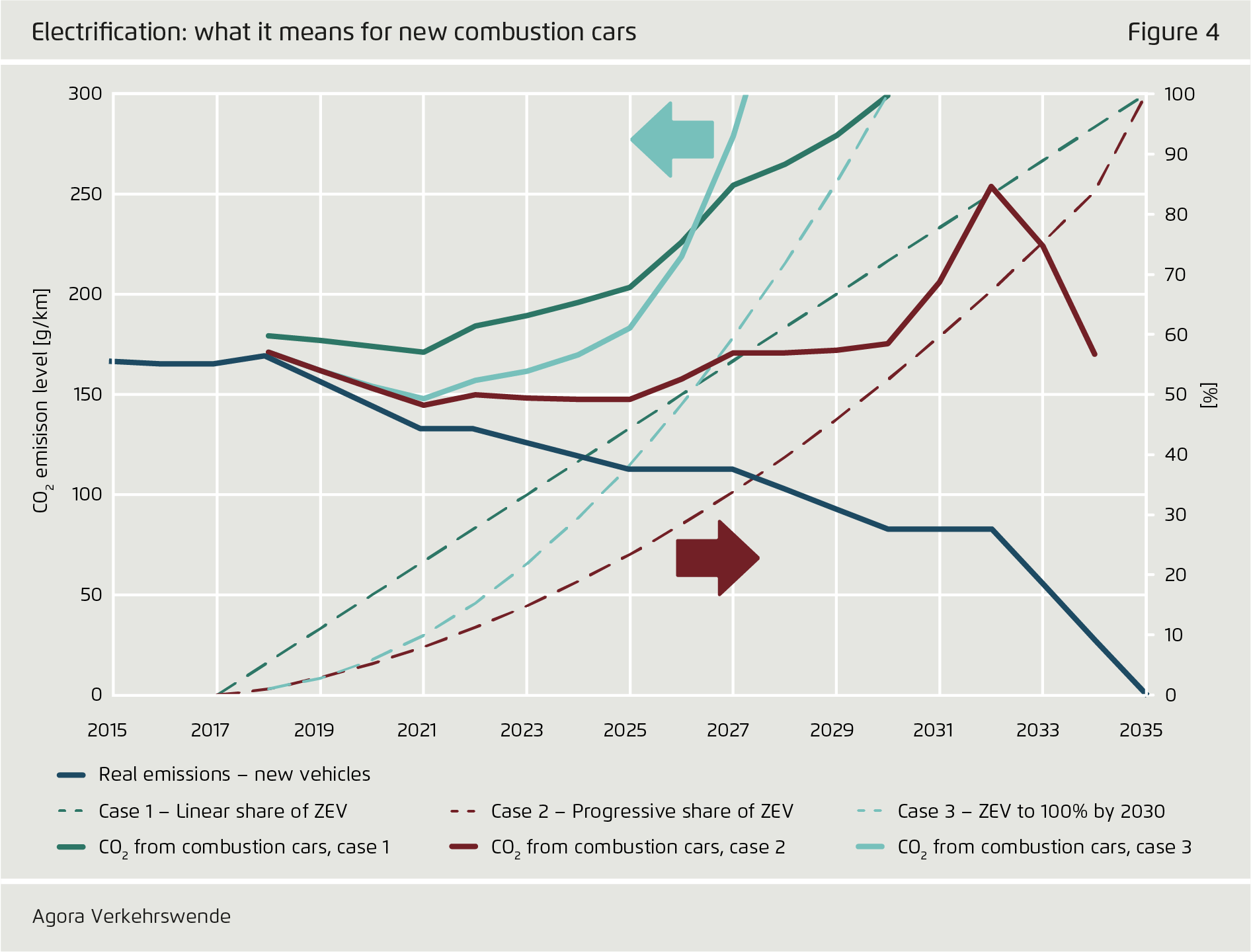

A license for gas guzzlers. One of these unwanted effects is that rising shares of ZEVs mean rising permitted emission levels for combustion cars, as outlined in the beginning. The next graph investigates the degree of that, looking at three different speeds of penetration of ZEVs. Case 1 is a linear rise in the share of ZEVs, from around zero in 2017 to 100% in 2035. Case 2 is a progressive rise, starting somewhat more slowly and then building up until again hitting 100% in 2035. Some people have indicated that the switch to full electrification might have to happen much earlier14, not least because there are also political targets to meet for the year 203015. Case 3 therefore rises in a progressive fashion to hit 100% already in the year 2030.

The consequences for the emissions of combustion-driven cars are shown in the graph. Compare these to the dark line that indicates compliance of the whole car fleet with the legislation as estimated above. Don’t get hung up on the exact assumptions that produced this particular shape for indicating compliance. What matters is that in each case considered, the average emissions of the combustion cars are allowed to be substantially higher, yet in all cases the legislation is respected. The reality may turn out to be somewhere between these curves. If so, the coming years wouldn’t see much reduction at all in the CO2 emission levels of new combustion-driven cars. In other words, as the share of electric cars rises the legislation turns into a license to build gas guzzlers.

And that’s before we have even considered two features in the legislation that are meant to support the market introduction of zero and low-emitting vehicles (ZLEVs)16. For this simple analysis I have ignored them because they would require detailed assumptions about who sells what. In reality they will push the allowed emissions of combustion cars still higher.

Does this mean we should stop introducing electric vehicles? Noooo! Of course we need zero emission vehicles, the more and the earlier the better. What it means is that the legislation needs to be adapted in order to avoid this side-effect of the electrification that nobody ever wanted.

Does it matter? Some may argue that this is not a bug but a feature: from the start, the policy deliberately allowed cars with very different emission levels in order to ensure that all manufacturers could comply, and because for the climate it only matters what the fleet as a whole emits17. It’s true that the average emissions, taken over all new vehicles sold in a year, respect the legislation in each of the examples shown. For the industry this is convenient because it allows them to sell more high-emitting conventional cars such as SUVs with higher profit margins which makes it easier to finance the transition towards electrification. Some companies have explicitly made the enhanced sale of SUVs part of their strategy. But the net effect is still that combustion-driven cars are allowed to emit more CO2 than otherwise which has never been the intention. And there is a big risk concerning public perception, not least because SUVs have been shown to be a major factor in the increasing emissions of the transport sector worldwide18.

Another scandal in the making? To an outsider, the falling limit value curve would suggest that cars are getting more efficient and lower-emitting over time, and I have no doubt that this is what the public will expect to see as a result. It was most certainly the understanding of the lawmakers who adopted the legislation. Instead, there is a risk that we may see the opposite as described. This is reminiscent of what happened with the standards for nitrogen oxide emissions (NOx) from diesel cars. They were tightened in successive stages, from Euro 1 through to Euro 6, with each stage painstakingly and controversially negotiated. Each time lawmakers thought they had tightened the standards, yet the nitrogen oxide emissions from diesel vehicles did not match that decline in reality19. I know – we can’t really compare these cases because there was also criminal misconduct involved in the diesel scandal. But the scandal also brought to light what only the experts knew until then: that a lot of the discrepancy between the laboratory tests and the emissions in the real world was legal. This was because of an obscure and complicated test procedure with lots of flexibilities and loopholes. It undermined trust in the ability of legislators to regulate the environmental performance of big companies. While it may have been good for the balance sheets of those companies in the short term, it also cost them a lot of public trust.

As illustrated above, the allowed emission surplus for combustion cars is quickly becoming excessive as the share of zero emission cars increases. We cannot assume that the public would miss this, which raises the spectre of another public backlash at a time when the industry is still reeling from the diesel scandal and in need of rebuilding its credibility. It would send a very strange signal if the legislation continued to allow the car sector to emit more in order to emit less.

A way forward: supplementary standards. The key provision in the legislation is the limit value on the average emissions taken over the whole fleet of a manufacturer. It incentivizes the market introduction of zero emitting vehicles which relaxes the standard for the combustion cars. What is missing are safeguards to prevent this effect from getting out of hand. One way of achieving this could be in the form of supplementary requirements that apply separately to the average emissions of each subgroup of vehicles. Those vehicles that actually emit CO2 would be subject to some form of supplementary CO2 limit value. This would preserve manufacturers’ flexibility to sell a wide range of different vehicles while preventing excessive emissions. Zero emission vehicles, for their part, could be subjected to efficiency rules with a stringency similar to that implied in the CO2 limits for the combustion vehicles20, as I have argued earlier.

Conclusion. With electric cars poised to enter the car market in substantial numbers, it becomes clear that the current way of legislating the CO2 emissions of light-duty vehicles has a weakness as regards the emissions of combustion cars21. The European Green Deal has advanced the revision of the Regulation to June 2021. That comes just in time. Introducing a supplementary level of regulating combustion-powered vehicles and zero emission vehicles, in addition to the established fleet average standard, could offer a chance to make each category more efficient in itself. This could help to avoid a surge in high-emitting vehicles that would undermine public trust further and lead to unnecessary emissions, while zero emission vehicles would also start to see efficiency requirements.

1 The legislation regulates the CO2 in the exhaust emissions of cars, and electric vehicles don’t have exhaust emissions. Of course the generation of electricity is causing emissions and there is a lively debate as to the real climate impact of electric cars today. However, the generation of electricity is one of the sectors covered by the European emissions trading scheme (ETS). The total emissions of greenhouse gas emissions from the sectors covered by the ETS are capped. This means that for each additional tonne of CO2 caused by the rising demand for electricity from electric cars, one tonne less is available for all the other sectors covered by the ETS. In that sense, electric cars in the EU are zero-emitting on a net basis already today.

2 Generally, if the share of ZEVs is x, then combustion-powered cars are allowed to emit on average x/(1-x) times more than the limit value.

3 Regulation (EC) No 443/2009

4 With a phase-in until 2015

5 The second stage was initially subject to a review. That review confirmed the value, although it added a delay of one year in the form of a phase-in: in 2020, only 95% of a manufacturer’s newly registered cars will have to meet the fleet average CO2 emission standard. From 2021, the standard applies to 100%.

6 The old and unrealistic New European Drive Cycle (NEDC) is replaced by the new World Light-duty Test Procedure (WLTP).

7 ICCT (2019): From laboratory to road: A 2018 update. https://theicct.org/publications/laboratory-road-2018-update

8 Stewart et al 2015, as quoted in ICCT (2019): From laboratory to road: A 2018 update

9 COM(2019) 640

10 Some see synthetic fuels for combustion engines as part of the solution. I don’t share that view, but even if we assume for the sake of argument that they are, it does not matter for the current discussion. If a certain share of the combustion cars would be declared “zero emission” by linking them to a certain production volume of synthetic fuel, they would appear as zero emission vehicles in the discussion that follows. The conclusions for the remaining combustion cars that run on fossil fuels remain unchanged.

11 Based on a simplified calculation that ignores the emissions of cars more than 14 years old.

12 For the Chinese New Energy Vehicle mandate, see e.g. https://theicct.org/publications/china-nev-mandate-final-policy-update-20180111

13 For a bottom-up analysis of the situation for the German manufacturers, see https://www.agora-verkehrswende.de/en/publications/entering-the-home-stretch/. A top-down assessment on the EU level is found here: https://www.transportenvironment.org/publications/mission-possible-how-carmakers-can-reach-their-2021-co2-targets-and-avoid-fines

14 For example, Peugeot’s CEO Jean-Philippe Imparato at the Brussels Motor Show.

15 The European Green Deal also envisages tightening the target for reducing the EU’s emissions for the year 2030 from 40% to at least 50% and towards 55% compared to 1990. The German government is aiming for 10 million electric cars on the road in 2030. Assuming an exponential build-up, the share of electric cars among newly-sold cars in the year 2030 itself will already have to reach around 60% in Germany, which implies full electrification shortly thereafter.

16 ZLEVs are defined to emit no more than 50g/km. In practice these are electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles. The so-called ZLEV factor rewards manufacturers who sell more ZLEVs than a certain benchmark by relaxing their specific emissions target even further, by a maximum of 5%. The degree to which this happens depends on the type of ZLEVs in a manufacturer’s fleet – it is most effective for electric cars and less pronounced for plug-in hybrids. The other feature takes the form of so-called super-credits that apply during the first three years from 2020. They allow a manufacturer to count each ZLEV as if it was more than one vehicle, thus lowering the manufacturer’s average emissions.

17 It also matters how much each car is driven, and bigger cars tend to be driven longer distances. The legislation does not address this aspect. It thereby contains an inherent bias in favour of larger cars.

18 IEA World Energy Outlook 2019. https://www.iea.org/topics/world-energy-outlook

19 The story is different for the pollutant standards for petrol cars which are an unmitigated success, and also for the emission of particulate matter from diesel cars.

20 The role of plug-in hybrid vehicles would require special attention as they tend to be large and heavy cars with very low certified emissions.

21 There are many more topics that require careful scrutiny, such as how to handle plug-in hybrid vehicles and all the other issues the Commission is bound to look at in accordance with Article 15 of the Regulation.